Exchange Funds Explained: Diversify Without Paying Capital Gains Tax

If you’ve accumulated a large, concentrated stock position, perhaps from an IPO, acquisition, or years of stock-based compensation, you’ve likely faced the challenge of diversification. Selling those shares can trigger significant capital gains taxes, making it difficult to rebalance your portfolio efficiently.

One option that investors sometimes use to diversify without immediately selling their shares is an exchange fund.

What Are Exchange Funds?

Exchange funds, also known as swap funds, are investment vehicles that allow investors with concentrated stock positions to diversify their holdings without selling their shares and triggering capital gains taxes.

Instead of selling your stock, you contribute your shares into a pooled fund. The fund combines your stock with shares from other investors to create a diversified portfolio. In return, you receive shares of the fund representing your proportional ownership of the pooled assets.

After typically seven years, you can redeem your shares and receive a basket of diversified securities. Importantly, capital gains are not eliminated — they’re deferred. Your original cost basis carries over to your new diversified basket.

How Exchange Funds Work

Here’s a simplified breakdown:

Multiple investors contribute their individual stock holdings into a single partnership or fund. The fund issues shares to each investor in exchange for their stock. After the required holding period (usually seven years), investors redeem their shares for a diversified basket of securities. Taxes are deferred until those new securities are sold.

This structure allows for immediate diversification while postponing tax liabilities.

IRS Rules and Requirements

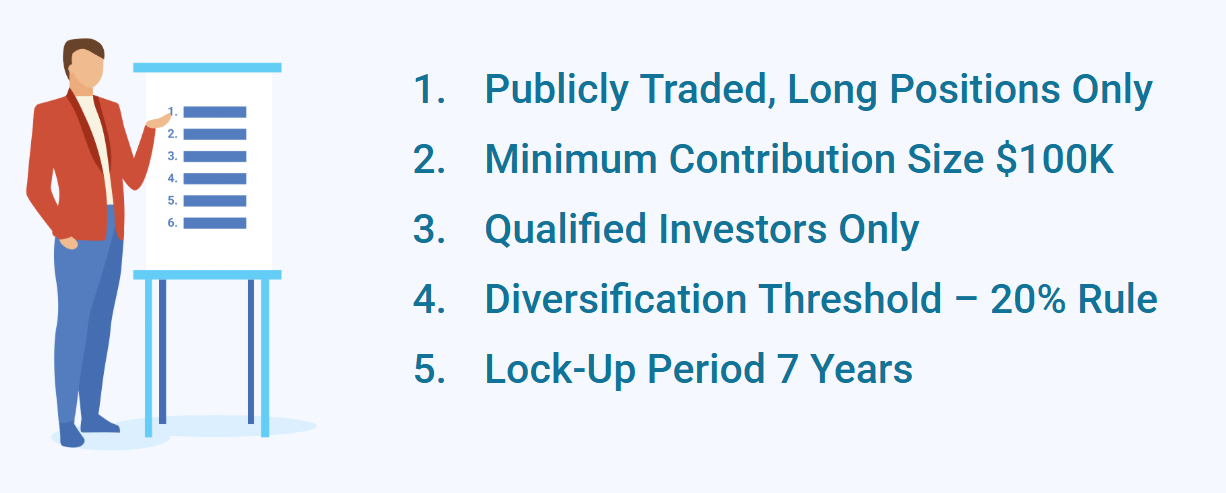

Exchange funds aren’t a free-for-all. The IRS sets clear rules to preserve their tax-deferred status:

Qualified Assets Only

Contributions must be publicly traded, long-only, fully vested U.S. securities.

Private shares, restricted stock, and stock options can’t be used.

Minimum Contribution Size

Traditionally, exchange funds were only available through institutional channels with high minimums — typically $1–$5 million per position. Recently, however, FinTech platforms have started offering exchange funds to DIY accredited investors, sometimes with entry points as low as $100,000.

Accredited or Qualified Investor Requirement

Exchange funds are private placements under Regulation D. You must be either an accredited investor (net worth over $1 million excluding primary residence, or high income), or a qualified purchaser (over $5 million in investable assets).20% Rule

At least 20% of the fund’s assets must be invested in non-publicly traded property — typically real estate or private equity. That’s why even if a fund claims to “track the S&P 500,” part of it will always include real estate holdings.

7-Year Lockup Period

Investors must stay in the fund for at least seven years to receive the full tax benefits.

Tax Treatment and Reporting

While exchange funds are designed for tax deferral, you may still owe small amounts of income tax along the way as they are usually structured as limited partnerships (LPs), which means pass-through taxation of income.

Exchange Funds distribute K-1 forms, often in March or April, which can delay filing of your tax return.

Fees and Costs

Exchange funds are not cheap. They typically charge high management and administrative fees, which can reach hundreds of thousands of dollars over the investment period. Before investing, it’s crucial to:

Review the total expense ratio.

Model out net-of-fee returns.

Ensure the tax deferral benefit outweighs the cost.

Who Should Consider Exchange Funds?

Exchange funds can make sense for three main types of investors:

Tech employees with concentrated stock positions often from IPOs, acquisitions, or long-term equity compensation.

Long-term investors with low cost basis. Families who’ve held stocks for 20–30 years and want to diversify without triggering taxes.

Investors not planning charitable giving. If philanthropy is part of your plan, strategies like donor-advised funds or charitable remainder trusts may be more efficient.

When Exchange Funds Don’t Make Sense

Despite the tax deferral, exchange funds aren’t always beneficial. They may not make sense if:

Your cost basis is relatively high, reducing your unrealized gain.

You expect to be in a lower tax bracket soon (for example, after retirement).

The fund fees outweigh the diversification and deferral benefits.

You may need access to the money before the seven-year lockup ends.

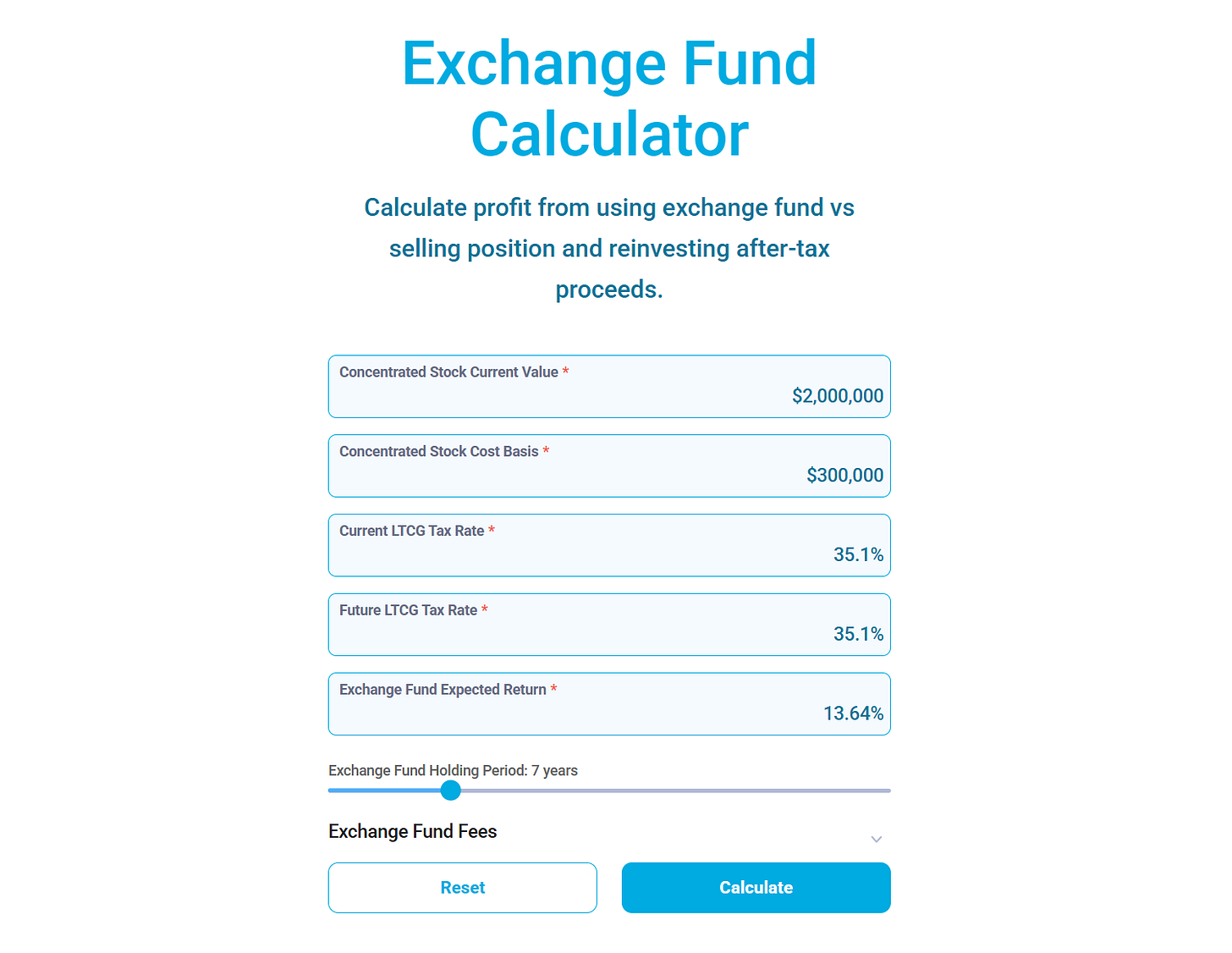

You can use our Exchange Fund Calculator to model your own scenario and see if it makes sense for you.

The Bottom Line

Exchange funds can be a powerful tax-deferral and diversification tool for investors with highly appreciated, concentrated stock positions — but they come with complexity, high fees, and long lockups. Before committing, it’s wise to:

Build a financial plan.

Model out costs, tax scenarios, and returns.

Compare with alternatives like charitable trusts or structured sales.

Used thoughtfully, exchange funds can help preserve wealth, reduce risk, and defer taxes — but they’re not for everyone.

Hi all,

Correct me if I'm wrong, but another problem with exchange funds could be the portfolio assets one exchanges into...for example, exchanging NVDA stock with a low cost basis may not make sense if the "diversifiers" in the exchange fund are all stocks like YELP, Pets.com, etc. And I would guess there is no real way of knowing what you're exchanging for before the fact. Correct.

Specifically, isn't the exchange fund user making a bet that the future performance of the diversifying assets in the fund will not significantly under-perform the asset added to the fund?

Brian